Unifying Cybersecurity: Why IT and OT Can’t Stand Alone

Public utilities and critical infrastructure operators face a unique challenge of securing both traditional IT systems and operational technology (OT) environments. These environments differ in design, function, and risk tolerance and were once treated separately. This isolation is no longer practical given the increased commonality of shared controls, systems, and enterprise risk. Managing these programs independently can lead to gaps in protection, duplicated efforts, confusion during incidents, and a fragmented view of cybersecurity risk.

As operational systems become more connected, the risks that traditionally targeted IT such as ransomware, credential compromise, and supply chain vulnerabilities now threaten OT as well. The need for a consistent approach to risk management, policy enforcement, and control implementation has never been greater.

Building that consistency requires more than a collection of tools. It requires a structured approach that draws from proven frameworks, practical control sets, and clearly defined standards. The right combination can help utilities unify their cybersecurity efforts, simplify compliance, and build a program that grows with the organization.

Understanding which resources to use and how they fit together is where the real work begins

Building a Blueprint: The Case for Using a Framework

A cybersecurity framework gives structure to a program that might otherwise develop through isolated fixes, vendor-driven tools, or audit findings. Without a framework, organizations often rely on informal practices that are difficult to scale, evaluate, or align with enterprise risk. A well-chosen framework helps set priorities, coordinate security efforts, and ensure that cybersecurity activities support the organization’s broader mission.

For utilities and other critical infrastructure providers, a framework also supports regulatory compliance, improves communication across departments, and enables long-term program growth. It helps organizations identify what protections are in place, where gaps remain, and what actions are most critical.

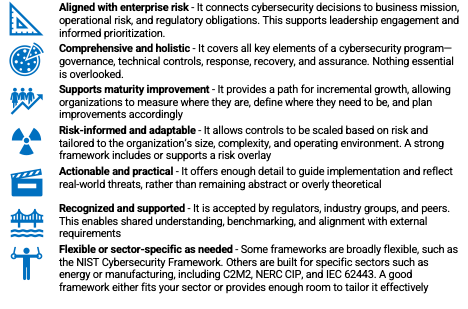

A good cybersecurity framework has several important qualities: including alignment with enterprise risk, a comprehensive program, supporting maturity improvement, risk-informative, actionable, recognized, and flexible.

Choosing a framework with these qualities helps ensure the cybersecurity program is not only complete but also aligned with risk, sustainable over time, and appropriate for the organization’s environment.

Speaking the Same Language: Frameworks, Controls, and Standards Explained

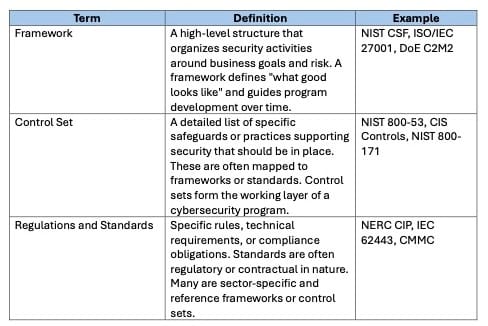

Although often used interchangeably, frameworks, control sets, and standards each play a distinct role in organizing a cybersecurity program. Confusing them can lead to poor tool selection, wasted effort, or gaps in coverage. Understanding how they differ helps organizations choose the right combination based on their needs and maturity.

Here is the difference:

Frameworks provide the strategic structure. Control sets fill in the operational details. Regulations and standards codify external expectations and often carry audit, certification, or enforcement requirements. A mature cybersecurity program will typically use all three: frameworks for structure, control sets for implementation, and standards or regulations to meet external obligations.

From Parallel to Unified: Aligning IT and OT Security Efforts

In many utilities and critical infrastructure environments, IT and OT systems have been managed under separate security programs. OT systems were once isolated, slow to change, and largely disconnected from enterprise networks. That model is changing. Many OT environments now include remote access, cloud integration, and shared infrastructure with IT, increasing both efficiency and risk.

OT systems rely on digital infrastructure for automation, data exchange, and centralized monitoring. IT systems often manage the credentials, analytics, and cloud services that support OT operations. As a result, threats like ransomware, credential theft, and supply chain compromise now move across both environments. Risk management, monitoring, and incident response must be coordinated to be effective.

Managing IT and OT security programs independently can lead to gaps in protection, duplicated efforts, confusion during incidents, and a fragmented view of enterprise risk. In contrast, a unified cybersecurity program improves coordination, simplifies oversight, and supports a consistent response to threats that affect both business operations and physical systems.

A unified program does not require identical controls or tools across environments. It requires shared governance, coordinated planning, and consistent risk analysis. Frameworks that support both IT and OT functions make this convergence possible without ignoring the differences that remain.

Choosing the Right Tools: What’s Out There and What Fits

To support a unified program, organizations need a common structure. That begins with selecting the right frameworks, control sets, and standards. Each of these tools serves a different purpose, and no single one provides everything needed to build a complete cybersecurity program. In practice, most organizations will use a combination of these resources.

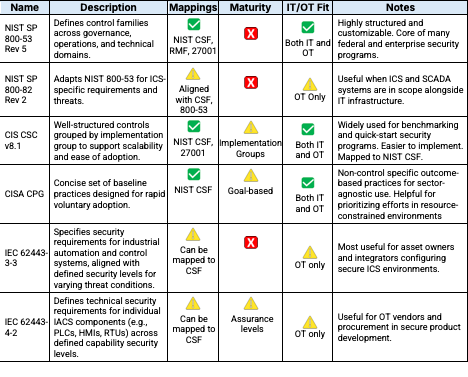

Below is a summary of widely used frameworks, control sets, and regulations or standards, with a focus on their relevance to IT and OT environments in the utility sector.

Frameworks

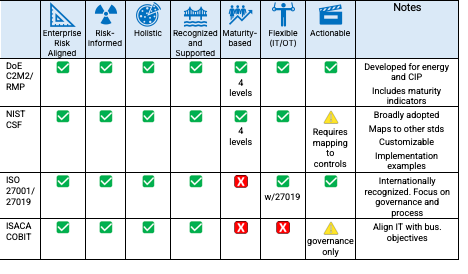

For organizations seeking to unify their cybersecurity programs across IT and OT environments, four frameworks stand out for their broad adoption and sector relevance:

- NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 – Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 2.0, February 2024

- DOE C2M2 – Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2) Version 2.1, July 2021

- ISO/IEC 2700:20022 – Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection – Information Security Management Systems – Requirements, October 2022 with ISO/IEC 27019:2017 – Information Security Controls for the Energy Utility Industry, 2017 and

- ISACA COBIT – COBIT 2019 Framework: Governance and Management Objectives, COBIT 2019

These frameworks differ in origin and focus, but each supports a structured, risk-informed approach to cybersecurity. All four are aligned with enterprise risk, helping organizations tie security decisions to operational priorities and regulatory requirements. NIST CSF and DOE C2M2 are especially strong in supporting program maturity, offering clear tiers or domains that guide incremental improvement. ISO/IEC 27001 provides globally recognized certification and a formal management system structure, while COBIT excels at aligning cybersecurity governance with business objectives. In terms of comprehensiveness, all four address key program domains such as governance, technical safeguards, response, and recovery, though NIST CSF and C2M2 are more directly actionable for operational environments. Finally, while COBIT and ISO/IEC 27001 are broadly applicable across industries, NIST CSF and DOE C2M2 provide greater flexibility or sector-specific tailoring for critical infrastructure operators. Together, these frameworks offer complementary strengths that make them particularly well suited for guiding a unified cybersecurity strategy.

Control Sets

In addition to broad frameworks, many organizations rely on control sets to populate the frameworks and to define specific safeguards they expect to implement. A control set translates high-level priorities into concrete actions (e.g., configurations, restrictions, processes, and verifications) that directly shape security operations. For a unified IT and OT environment, the right control set should be both technically sound and flexible enough to address diverse systems. Six controls sets are generally applicable and useful to adopt for framework population:

- NIST SP 800-53 Rev 5 – Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations

- NIST SP 800-82 Rev 3 (Draft) – Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security

- CIS Controls V8.1 – Center for Internet Security Critical Security Controls for Effective Cyber Defense, Version 8.1

- CISA CPG – Cybersecurity Performance Goals (CPG)

- IEC 62443-3-3 – Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems – Part 3-3: System Security Requirements and Security Levels

- IEC 62443-4-2 – Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems – Part 4-2: Technical Security Requirements for IACS Components

Some control sets, like NIST SP 800-53 or CIS Controls, are broadly applicable across sectors. Others, like NIST SP 800-82 or IEC 62443, offer OT-specific guidance. CISA’s Cybersecurity Performance Goals provide a prioritized, outcome-driven baseline especially helpful for critical infrastructure operators. These control sets differ in scope, complexity, and regulatory context, but each plays a vital role in strengthening a cybersecurity program by giving clear direction for implementation and assessment.

Regulations and Standards

NERC CIP is the primary regulatory standard for electric utilities that operate within the North American bulk electric system. It establishes baseline cybersecurity requirements for protecting critical infrastructure and is a mandated component of the cybersecurity program for organizations in this space.

Many utilities also operate in complex environments and may be subject to additional regulations and standards depending on the types of data they manage, the services they provide, and their organizational structure. A utility that accepts payment cards may need to comply with PCI DSS. If it handles employee or customer health information, HIPAA may apply. Publicly traded utilities are subject to SEC cybersecurity disclosure rules. Utilities that collect or process personal information may fall under privacy laws such as GDPR, TXDPA, or NY SHIELD. Each utility must determine which regulations are applicable and ensure their cybersecurity program accounts for those requirements. A practical approach is to map applicable regulations to the organization's selected cybersecurity framework to create a unified, efficient compliance strategy.

From Compliance to Capability: Using Frameworks to Grow

A cybersecurity framework should be more than a tool for passing audits. The most effective programs use frameworks to guide measurable improvement, not just compliance. Maturity-focused frameworks help organizations assess where they are, set goals, and plan realistic paths toward a stronger cybersecurity posture.

Frameworks such as NIST CSF and C2M2 include features that support long-term development. These models help organizations define a target state, evaluate current capabilities, and build a roadmap for growth over time. They allow progress to be tracked in a structured way, which supports both strategic planning and operational accountability.

Other standards, such as IEC 62443, do not provide a maturity model but do include structured security levels that define required protections based on risk. These can help organizations set appropriate control expectations, particularly in OT environments, but they do not measure program growth over time.

Using a maturity-based framework improves consistency and alignment across teams. Rather than reacting to incidents or audit findings, organizations can adopt a deliberate improvement plan based on risk, mission, and operational needs. This leads to programs that are more resilient, better aligned, and easier to communicate to both technical and non-technical stakeholders.

Putting It All Together: First Steps Toward Integration

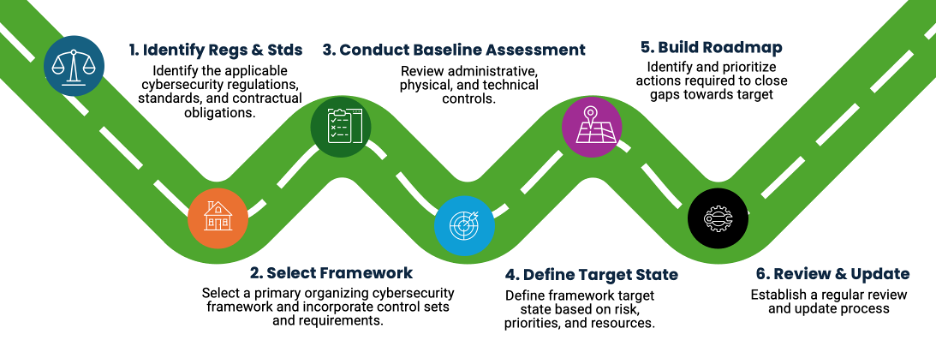

Building a unified cybersecurity program for both IT and OT starts with establishing a common structure for assessment and planning. This involves identifying the full set of requirements the organization must meet, selecting an organizing framework, and using that framework to evaluate current capabilities across environments. A phased approach makes this manageable and helps align improvements with real operational needs.

Start by identifying all applicable regulations, standards, and contractual obligations. These may include NERC CIP, CMMC, ISO 27001, or industry-specific guidance such as IEC 62443 or DOE RMP. This step ensures the program accounts for mandatory requirements, as well as widely accepted expectations for security and risk management.

Next, select a primary organizing framework, such as NIST CSF or C2M2, and incorporate applicable control sets and regulatory requirements into that framework. This creates a single structure for evaluating the cybersecurity program holistically, rather than managing IT and OT requirements separately.

With that structure in place, conduct a baseline assessment. This includes reviewing governance practices, policies, processes, technical controls, monitoring, training, and incident response. The assessment should also include a detailed control inventory to determine what protections are already in place. To ensure objectivity, this baseline assessment is best performed by an independent party. In-house assessments often reinforce existing assumptions and may overlook issues that have become normalized over time. An external perspective helps surface blind spots, challenge embedded practices, and provide a more accurate foundation for planning improvements.

Once the baseline is understood, define a target state based on risk, business priorities, and available resources. From there, build a roadmap that identifies and prioritizes the actions needed to close the gaps and strengthen the program over time.

Finally, establish a regular review and update process. A cybersecurity program should be a living effort that evolves alongside changes in technology, risk, and operations.

A Program with Purpose: Unifying Strategy, Structure, and Security

Cybersecurity programs are most effective when they serve more than a compliance function. In public utilities and other critical infrastructure environments, the program must support operational reliability, safety, and public trust. That requires a clear strategy, consistent structure, and practical implementation.

Using a recognized framework provides the structure. Aligning that framework with applicable control sets and regulatory obligations ensures the program is complete. Performing a unified assessment across IT and OT ensures that risks are managed cohesively, without silos or conflicting priorities. And building a roadmap tied to business risk creates the momentum needed for sustained progress.

This approach replaces reactive or checklist-driven efforts with a program that supports long-term capability. It encourages investment in areas that matter most, from monitoring and response to training and governance. It also improves coordination between technical teams, leadership, and regulators, making the program easier to manage and easier to explain.

A unified cybersecurity program does not mean treating every system the same. It means organizing efforts under a shared mission: protecting the systems that deliver essential services while supporting the broader goals of the organization. That clarity of purpose is what turns a set of controls into a meaningful program.