The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) is a favorite among security leaders, compliance officers, and regulators. It has been adopted by more than half of Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the United States, and surveys suggest that between 32 percent and 50 percent of U.S. businesses now use it as their primary cybersecurity framework. With broad adoption across sectors and government, it is often treated as a gold standard.

But the CSF's popularity conceals a problem: its most misunderstood feature, the Tier system, is frequently misused. The result is overconfident self-assessments, misleading board reports, and cybersecurity programs that appear far more robust than they are.

This misunderstanding is not just academic. It undermines cybersecurity governance, confuses regulatory interpretations, and drives misaligned investments. In this article, we will examine the root of the confusion, explore real-world examples, and offer a practical fix.

Understanding the Purpose of the CSF

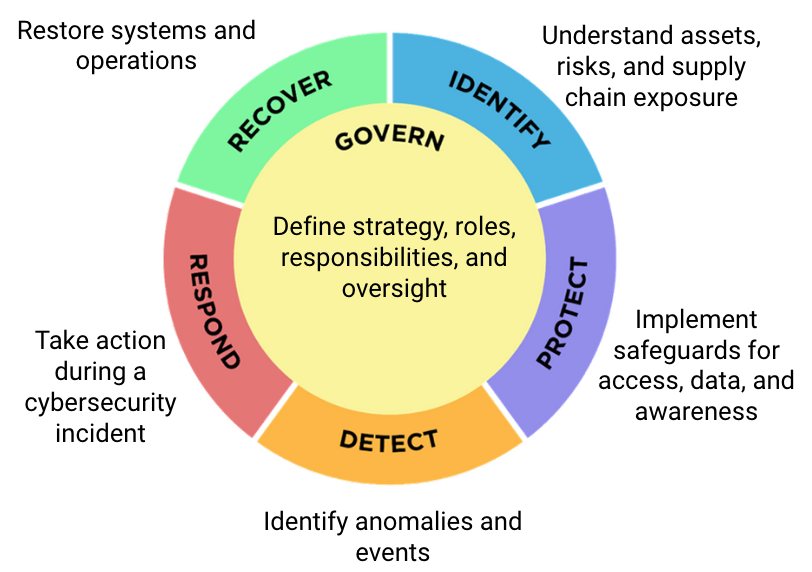

The NIST CSF was first released in 2014 and updated in 2018 and 2024 (as version 2.0). It provides a high-level framework for managing cybersecurity risk across six Functions.

Each Function is divided into Categories and Subcategories that guide organizations in building and assessing their cybersecurity capabilities. These elements are intentionally flexible and can be aligned with specific control sets such as NIST SP 800-53, ISO 27001, or CIS Controls.

The CSF is not a control catalog. It does not specify what technical safeguards should be in place or how effectiveness should be measured. Instead, it provides a structure for organizing and evaluating a cybersecurity program at a strategic level.

The Role and Misuse of Tiers

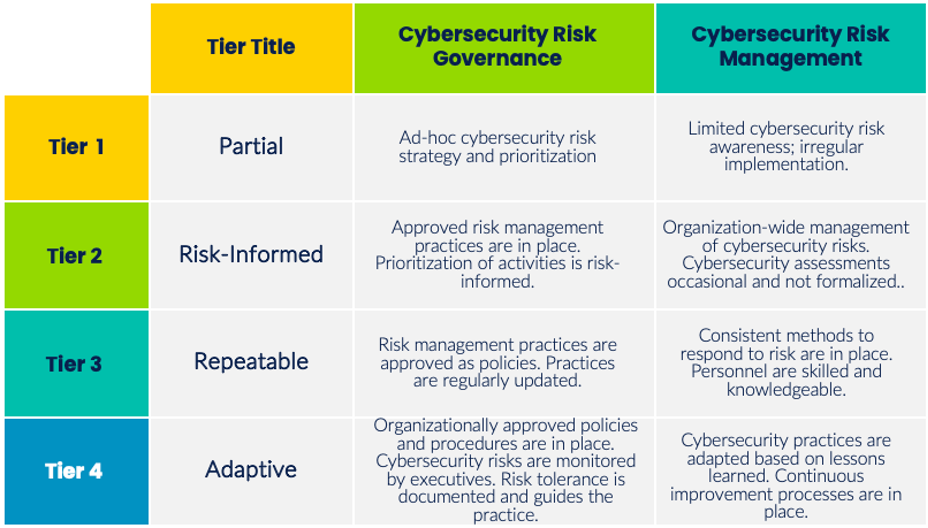

The most misunderstood part of the CSF is the Tier system, which is intended to describe how deeply cybersecurity risk is integrated into an organization's governance and risk management practices. The Tiers are illustrated below.

These tier terms (e.g., ad-hoc, repeatable, continuous improvement) resemble maturity levels, and many organizations, assessors, and auditors treat them that way. But NIST is clear: the Tiers are not maturity levels and do not indicate control performance or cybersecurity effectiveness.[1]

According to NIST, the Tiers “can be applied to CSF Organizational Profiles to characterize the rigor of an organization’s cybersecurity risk governance and management practices.” They are intended to supplement risk management processes, not replace them.

In practice, however, the resemblance to traditional Capability Maturity Models (CMMs) leads many organizations to conflate the two. A Tier 4 designation is commonly interpreted as evidence of a highly effective cybersecurity program, even though the CSF makes no such claim.

The Industry Disconnect

Despite what NIST says, the market behaves differently. Security leaders often use the CSF as a de facto control framework and expect assessments to include maturity scoring, implementation evidence, and validation of control effectiveness. That expectation is reinforced by consultants and vendors who build maturity models into their CSF-based assessment tools and reports.

The result is an ecosystem that uses the CSF in a way that goes beyond its design but without disclosing the leap. This disconnect leads to serious problems:

- Self-assessments and third-party reviews inflate maturity scores by rating cybersecurity risk integration, not actual control strength.

- Boards and executives are misled into thinking a Tier 3 or Tier 4 rating means their controls are effective and tested.

- Regulators and auditors encounter CSF Tier ratings in place of required control evaluations or risk analysis.

This is not just a theoretical concern. Here are examples from three sectors where CSF misuse had real-world consequences.

Case Study 1: Utility Sector

A large regional utility adopted the CSF and conducted an internal self-assessment. It reported itself as Tier 3 (“Repeatable”) across all Functions and Categories, presenting this to its board as proof of strong cybersecurity maturity.

However, a subsequent regulatory audit revealed serious deficiencies: no formal vendor risk process, incomplete asset inventory for operational technology, and no validated backup restoration. The Tier 3 designation reflected governance integration (written policies and risk awareness), not actual control maturity or effectiveness. The board assumed Tier 3 meant controls were tested and working. The regulator forced remediation efforts that were costly and reputationally damaging.

Case Study 2: Healthcare Provider

A healthcare organization mapped HIPAA safeguards to the CSF and produced a Tier-based profile, claiming Tier 4 (“Adaptive”) in most Functions. This profile was presented to executives and auditors as evidence of strong cybersecurity controls.

Yet during a HIPAA audit, it was clear that key safeguards were missing: no formal risk analysis, no consistent incident tracking, and no structured security testing. The Tier 4 rating was based on governance practices (policies, awareness, leadership engagement), not on tested controls. Executives had equated Tier 4 with best-in-class control maturity, leading to overconfidence and compliance exposure.

Case Study 3: Financial Institution

A financial firm engaged a consultant to conduct a CSF-based assessment. The consultant used interviews and document reviews to assign Tier ratings, resulting in a Tier 4 profile that was reported to the board as evidence of a highly mature cybersecurity program.

Later, an internal review found significant control gaps: inconsistent third-party risk reviews, inadequate endpoint monitoring, and limited multi-factor authentication. The CSF assessment had never evaluated individual controls—it measured governance integration only. But the Tier 4 label was miscommunicated to executives as a guarantee of control strength and effectiveness. The board was surprised to learn that a Tier 4 designation could coexist with weak or missing safeguards.

The Need for a Better Approach

The problem is not with the CSF itself. It is a flexible, well-structured framework for organizing cybersecurity programs and identifying gaps. The problem is in assuming that the CSF can serve as a stand-alone tool for assessing maturity or control effectiveness.

Organizations that want to evaluate their cybersecurity maturity need a rubric that includes:

- Control implementation – including essential elements, completeness, and effectiveness reviews.

- Control testing and monitoring – including periodic testing, exception handling, and roles and responsibilities.

- Evidence of control effectiveness – including the collection and review of evidence.

- Formalized procedures and roles – covering the implementation of key policies and practices.

- Governance integration – including inter and extra organizational coordination.

These elements are not provided by the CSF directly. But they can be layered onto the CSF to build a more comprehensive assessment.

A Field-Tested Rubric

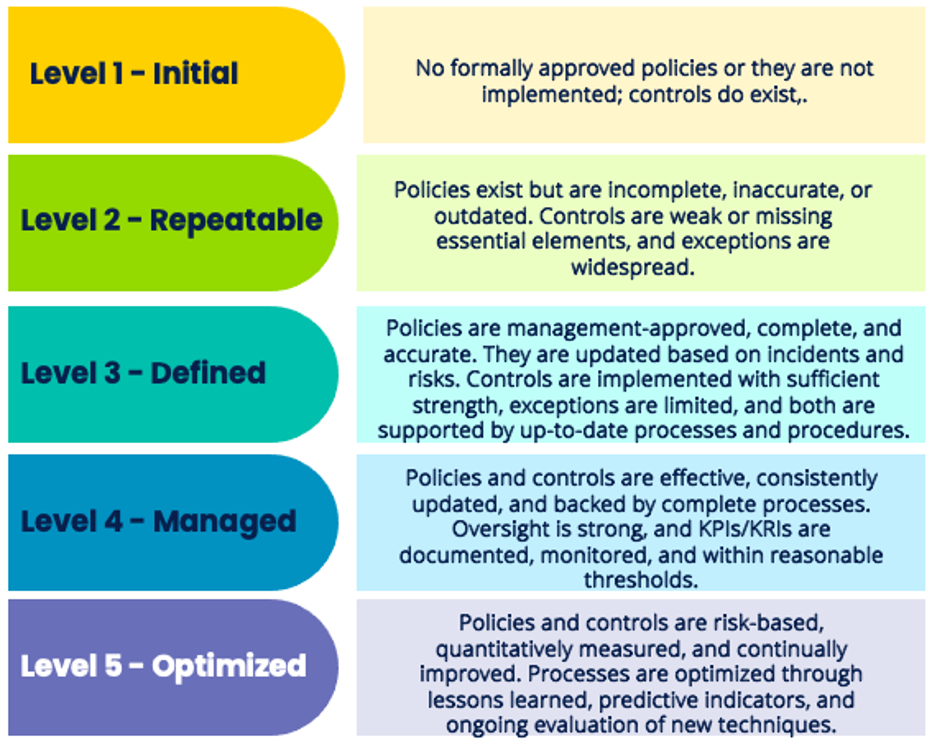

To properly measure program effectiveness, organizations can supplement the CSF with a cybersecurity-specific maturity rubric aligned to five levels. Unlike the Tier system, which describes governance integration, this rubric evaluates both policies and actual control implementation.

Using this rubric alongside the CSF allows organizations to assess maturity in a structured, transparent way. It highlights not only whether policies exist but also whether controls are implemented, monitored, and effective. This approach gives executives a more accurate picture of cybersecurity program health, produces actionable roadmaps, and avoids the pitfalls of relying solely on CSF Tiers.

Recommendations for Organizations

If your organization uses or is planning to use the NIST CSF, consider these best practices:

1. Use the CSF for Structure and Communication

Leverage the six Functions and their Categories to organize your cybersecurity program and guide strategic planning. Use CSF Profiles to compare current and target states and to communicate priorities in a structured, accessible way.

2. Treat the Tiers as Governance Indicators

Understand that CSF Tiers describe how deeply cybersecurity risk is integrated into organizational governance and risk management. They do not evaluate the quality, maturity, or effectiveness of specific controls.

3. Supplement with a Maturity Rubric

When assessing controls, apply a defined maturity rubric—such as the five-level cybersecurity maturity scale (Initial, Repeatable, Defined, Managed, Optimized). This allows evaluation of control implementation, effectiveness, and sustainability, which CSF Tiers do not provide.

4. Clarify the Assessment Lens

Be explicit about whether the assessment is measuring governance integration (via CSF Tiers) or control maturity and effectiveness (via a maturity rubric). Do not merge the two. If both perspectives are included, present them separately and clearly explain what each represents.

5. Communicate Clearly with Stakeholders

When presenting CSF results, be transparent about what is being measured. Executives, boards, and regulators should know whether scores reflect governance integration, operational maturity, or both—and how to interpret each.

6. Train Your Assessors

Ensure that internal and third-party assessors understand the distinction between CSF Tiers and maturity rubrics. Provide training on when and how to apply each, and how to communicate results consistently to stakeholders.

Final Thoughts

The NIST CSF remains one of the most valuable frameworks in cybersecurity. It provides a common language, supports alignment with other standards, and helps organizations navigate a complex threat landscape. But like any framework, it must be used correctly.

Treating the CSF Tier structure as a maturity model leads to dangerous misconceptions. A Tier 4 rating may reflect strong governance alignment, but it does not guarantee secure configurations, effective detection tools, or reliable incident response.

By supplementing the CSF with a transparent, structured maturity rubric, organizations can benefit from the CSF’s clarity while avoiding its most common misuse. The Tier trap is real, but with the right tools, it can be avoided.

[1] Look at the table and notice what a low bar Tier 3 is as defined by NIST (e.g. approved and updated policies, and knowledgeable personnel but not procedures, not metrics, no definition of risk tolerance, no lessons learned in place).